Remembering Mac Miller

October 8, 2018

I pull over as soon as I hear. Lying weakly against the car door, I’m struck by an overwhelming need to call someone and weep. But I’m not strong enough for tears. In fact, I can’t even muster words.

“Silence is all that I hear, listening close as I can.”

Mac Miller always took them right out of my mouth. As “Wings” — the serene hymn that hallmarks Swimming, Miller’s critically acclaimed third studio album — repeats on my car stereo for what feels like both the first and fortieth time, all notions of reality seem to escape me. I can’t shake the feeling that if I just close my eyes and listen hard enough, he’ll be there.

He always was before. We fans saw a part of ourselves in Mac, an undyingly genuine piece of shared consciousness lying somewhere in between our insecurities and delusions of grandeur. Where we often lacked the boldness to speak on these parts of our psyche — the security to face these insecurities — he did not.

Mac’s constant reinvention always felt innately human to me. He was never quite sure who Mac Miller was or what he thought about him. From the retrospectively inauspicious frat-rap of Blue Slide Park to the drugged-out haze of Faces, it often seemed as if being himself meant being someone else, his reflection in the mirror serving as a reminder rather than as an acceptance. For a whole generation of kids, this intrinsic uncertainty rendered him a sort of Holden Caulfield-esque hero, an outlet we could reach through every song. When he died, this heroism shifted to a martyrdom. The hope that he embodied is, both literally and figuratively, dead.

This year is decimating young hip-hop fans. Between Lil Peep, XXXTentacion, and now Mac Miller, the contemporary rap artists that we love so dearly can’t seem to escape the demons of addiction and violence that long plagued their predecessors.

This one feels different, though. The collective reaction to both Peep and X’s deaths was rooted in shock, our grief seemingly stymied by the disbelief inherent in their youth. They had just gotten here. How could they be gone?

But even at 26, Mac seemed to have been around as long as we can remember. He wasn’t larger than life. He was a part of it. Losing Mac feels like losing this close friend we were always supposed to meet; his — no, our — story isn’t, and never will be, finished. The immediacy of this reality is shattering in a way that fosters a sense of communal grief among us fans. When we found out about his death, the first call wasn’t “did you hear?”. It was “are you okay?”.

I wasn’t. I’m still not. And odds are, whenever this reaches you, I still won’t be.

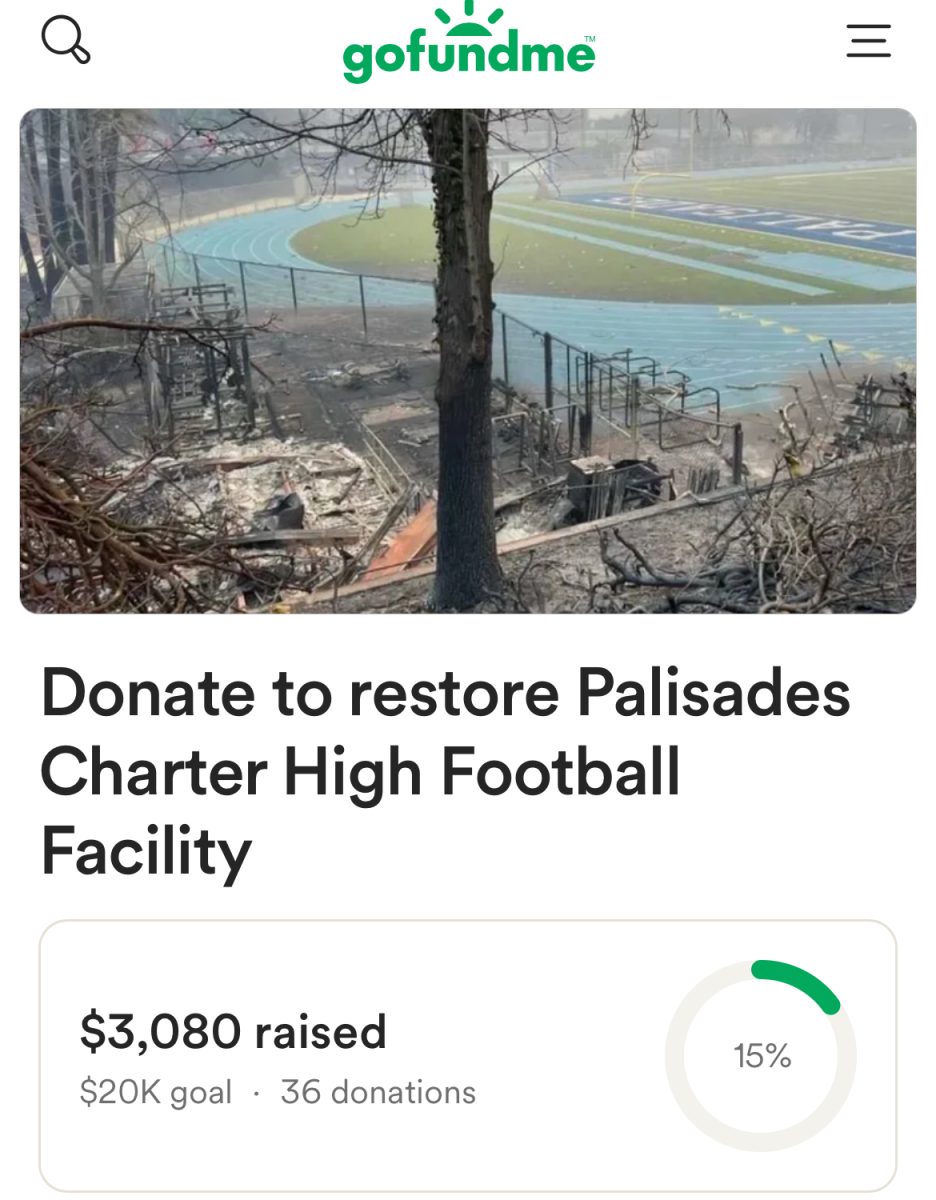

Mac’s death resonates with me in a viscerally personal way, and it should hit close to home for our entire community. It wasn’t six months ago that we witnessed the systematic creation of an abuse-ridden prescription drug culture right here at Pali. Many students nearly overdosed, and we lost a friend of the community.

We should consider ourselves truly blessed that this is the Tideline’s first obituary of the year. Addiction plays no favorites. There are no exceptions to its unrelenting grip. All of our students fighting addiction could have suffered Mac’s tragic fate.

Yet, in the context of his oft-publicized battle with addiction, Swimming seemed to portray Mac at his most content, something that makes his death so unfathomable. Expounding on the demons of his tumultuous breakup with pop star Ariana Grande and his subsequent May DUI arrest, the album is a diary of change as much as it is a sign of some sort of recovery.

Was he sober? Not completely. Was he happy? It came and went.

But did he know who Mac Miller was? Absolutely.

These metacognitive tendencies, the musings on drugs, life, and the meaning of it all, came to define his artistry as much as it haunted those who loved him the most. “You know what’s funny? I feel like the public perception of me varies based on who you ask,” Mac said in a Vulture profile published two days before his death. “No one’s ever really gonna know me. The people that would have the best chance of knowing me, that would like to, would be by listening to my music.”

But as much as we appreciated the music, we loved the man more. While I’ve cared about, admired and related to many artists, I’ve never quite been happy for one before. Swimming evoked those feelings about Mac for his fanbase. He carried a certain tranquility in his tone as he glided over Thundercat basslines and self-orchestrated horn sections, and the peace of mind he seemed to have found gave listeners a sense of solace that we clutched dearly. “You see me, and you, we ain’t that different,” he spoke tenderly on album highlight “2009”, a therapeutic catharsis of his former demons. “I struck the fuck out and I came back swingin’.”

Lines like that encapsulate the gravity of Mac’s loss more than any of my words ever could. Us fans and him, we really weren’t that different. In fact, our mental homogeneity effectively bridged the gap between artist and listener. Through the lens of our own trying times, seeing him find himself made everything seem a little less bleak.

And now, we must begin to deal with the harsh reality that Mac Miller has spoken his final words both to himself and to us. He’ll never get his fans through another day, at least not like he used to. The lyrics take on a new meaning now, his overarching motif of mortality a depressive reminder rather than a sign of hope.

“We strung out like a violin,” he raps on a track off 2012’s Macadelic mixtape. “Come back to life, then we die again. Little angel, where’s your halo? Somewhere above these horns.”

The song carries the haunting moniker of “The Mourning After”.

As I sit writing this, Mac Miller has been dead just over 36 hours. Overwhelmed with grief, I find both the song’s title and its lyrics to be uniquely fitting. For a long time, every morning will be ‘the mourning after’, a constant reminder that we will always be strung out on Mac’s proverbial violin.

Usually, when someone we love dies, we say that they’ve reached a better place. It doesn’t feel authentic to say that about Mac. Instead, I find myself trying to reconcile the placement of his halo over the horns of his addiction, the perception of the peace I believed he’d found with the reality of his end. It doesn’t feel right. I want to drown in the sorrow. But in these moments, I think about what Mac would do, and sometimes when I close my eyes real tightly, I can see him doing it right along with me.

He’d keep swimming.