The Future of Yearbooks

December 8, 2020

Student surveys, personal headshots, senior superlatives and spirit weeks — hundreds of memories compiled together into a paper-bound book creating a journal of students’ past year in high school.

The concept of yearbooks has been relatively the same since the beginning of education: paperback or hardcover books filled with representation of students’ hard work leading up to graduation. The first yearbooks were composed in the 1600s and were merely scrapbooks. Since photography was non-existent, students would fill their books with notes, articles, flowers and even hair to remember events.

Because of evolving technology, current students receive 300-page, laminated hardcover books filled with high-quality images and detailed captions.

But what happens to the beloved yearbook when students are not on campus, masks are mandatory and spirit days consist of online videos and photoshopped images?

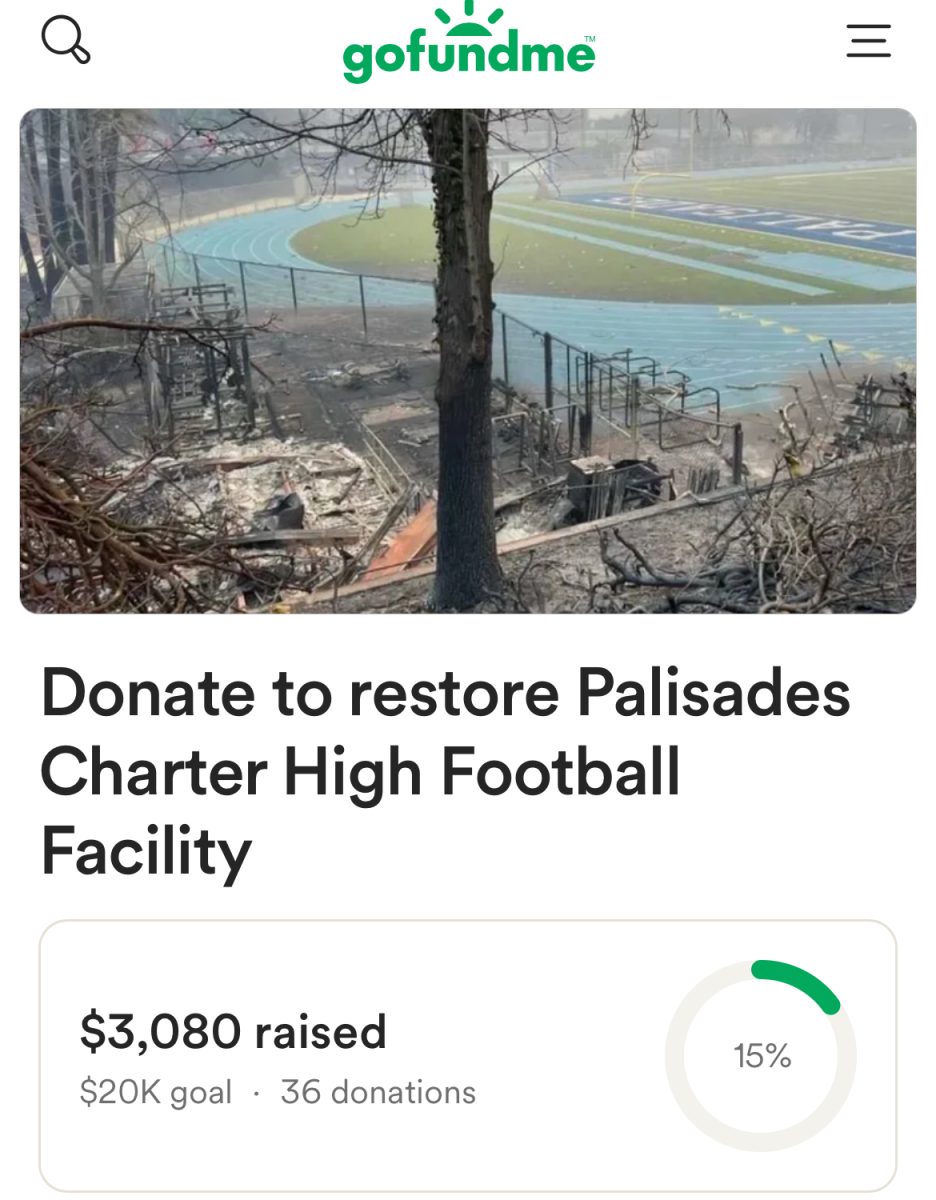

After the coronavirus pandemic devastated the country and sent students into mandatory lockdown in March, the 2019-20 Pali yearbook staff was left with a half-finished yearbook. Pages meant to be brimming with another three months of school, sports, senior days and clubs were empty. In the end, they replaced these pages with a “We’re sorry” memo and called it a year.

Eight months after that fateful day in March, the yearbook staff faces an unprecedented semester of Zoom classrooms, virtual team practices and online student surveys. Luckily, this is the generation of the digital age, and most, if not all kids have grown up surrounded by cellphones, social media and instant video.

Editor-in-Chief of Pali’s yearbook Samantha Wallace says that the yearbook staff is relying on students to volunteer to submit their own images to be included in the book. Although it is well-known that members of Gen Z love to take photos of themselves, yearbook’s Photography Editor Maxine Eschger says that filling the 300-page book is more difficult than it seems because photos must have students being “mindful of social distancing guidelines and wearing masks.”

This creates multiple obstacles for the yearbook staff to put together a coherent book full of student life. They’ve found that while students may take plenty of photos, many are too shy to send them in, and if they do send photos in, they are either too blurry to be printed or don’t meet the yearbook’s COVID criteria. Subsequently, the yearbook staff has had to improvise and find new ways to represent the student body.

According to Wallace, full-page survey segments will replace the pages that used to contain Pali sports, and instead of specific sections like “academics, student living [and] class portions…it’s going to be more related to seasons.”

Rick Steil, Pali’s yearbook advisor for more than a decade, says that “people with masks on tells a story of where we are at right now.” However, Steil is concerned that 20 years from now, flipping through a yearbook dotted with photos of students wearing masks is going to be like a guessing game of “Who’s that? Nice eyes.”

Even if the staff receives enough suitable photos, the yearbook may tell a story but will not serve its primary purpose. Instead of hundreds of smiling group photos, the 2020 yearbook will “feature more single shots, because if you’re not in a group you don’t need a mask,” Steil states.

In terms of clubs, members will be showcased in a screenshot of a Zoom meeting. This may be even better than normal group photos, Steil says,“because instead of wedging all the kids in the back,…every kid is gonna get the same amount of space.” Steil says that online platforms make it easier for students to organize a photo, without anyone having to physically go anywhere.

Next semester, the yearbook staff is hoping to take drive-by portraits of students. Freshman, sophomores and juniors can drive by Pali, hop out of their cars and quickly take their pictures for the yearbook headshots. Until then, the yearbook staff is adjusting, creatively filling pages.

Many students share pictures and messages on their personal Instagram pages, which basically acts as a real-time, virtual yearbook. Last year, a 2020 senior created the @paliseniors2020 Instagram account, which featured pictures of graduating seniors alongside the college they would call home for the next four years. Student-run clubs have also joined the Instagram bandwagon, with accounts like @palitraderjoesclub and @paliredcross using the platform to make announcements and provide updates.

Because of these accounts, the yearbook staff has had to find new ways to represent student-living. This may be the change this 400-year-old book needs.