Since Students are Earning Grades, Shouldn’t Teachers Be Getting Them, Too?

Learning is an agreement between two parties: the instructor who agrees to teach and the student who agrees to learn. Like any form of communication, instruction is an exchange, and in this case, it’s one in which the performance of each party is dependent on the other. However, our current grading system evaluates just one-half of this process, only grading students. But to get a true picture of what’s going on in the classroom, shouldn’t students grade teachers, too?

Whether using letter grades, grade-point averages (GPAs) or written evaluations, measuring student performance has been an integral part of education since the implementation of the modern grading system. The original goal of these evaluation systems was to quickly and efficiently evaluate students so they could enter the workforce. Since then, grades have become the primary form of feedback students receive, impacting their future careers and pursuits of higher education.

Seeing that we have a system in place in which teachers can assess student learning, it seems logical that we would also have one allowing students to evaluate their teachers’ instruction. I’m not suggesting students should be able to determine the fate of their teachers’ careers, but students should have an effective way to provide feedback to teachers and school administration about their experiences. What worked well? What was confusing? Is the textbook clear and informative? What external or online tools were most effective? I would imagine the answers to these questions would be just as valuable to teachers as grades are to students, not to mention the benefit to future generations of students.

According to The Universal Business School, Student Evaluations of Teacher Effectiveness (SETEs) were developed independently by educational psychologists Herman H. Remmers at Purdue University and Edwin R. Guthrie at the University of Washington in the 1920s. Since the 1960s, SETEs have become common in colleges as a way for professors to improve their teaching using student feedback. If student evaluations are useful to professors in higher education, why aren’t they also implemented in high schools? I would think that direct feedback from students, the ones spending time daily with their teachers, would provide greater insights into teaching effectiveness rather than tests, which is the main feedback tool that exists today.

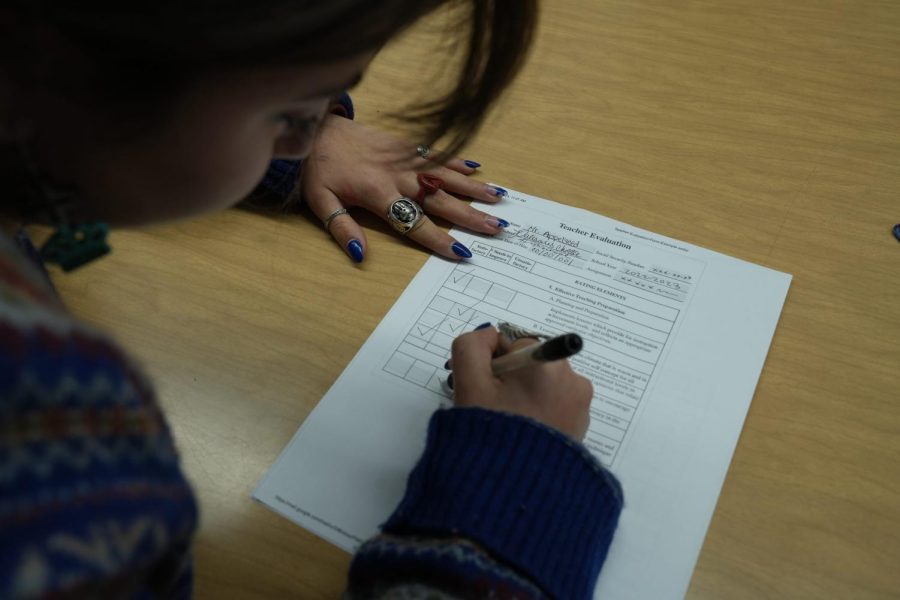

Algebra 2 teacher Stephen Matthews said that he uses periodic surveys in addition to test scores to measure the efficacy of his lessons.

“On average I give the students a survey, three or so times a year, asking them what’s really helping you, what’s not helping you, what suggestions do you have?” Matthews said.

Why isn’t this the norm? It shouldn’t be based on teacher discretion to decide whether to implement student evaluations. Imagine what education could become if students had a platform to communicate what works well in their classes with their teachers and administration.

Before 1987 when Neil D. Fleming, a teacher from New Zealand, introduced the VARK model of learning, not all educators understood that different students process information in different ways, according to the VARK Learning Styles. According to the VARK model, some students are visual learners while others are auditory or tactile learners and still others are read/write learners. What if students had more of a voice to express things like “I can’t just hear it, I need to see it” in a history classroom? Or they could fill out a form to tell a math teacher, “I need to know how this math problem applies to the real world in order to be successful at it.” Similarly, who decides the effectiveness of textbooks and other resources used in the classroom? Why isn’t the student, as the consumer of those resources, given an opportunity to provide their input — if not for the benefit of their own learning, to help improve the course for future students?

A major concern against student evaluations in high schools is that students simply aren’t mature enough to take teacher evaluations seriously. However, according to an article in The Atlantic, an experiment that involved a quarter-million students concluded that students as young as kindergarten were able to evaluate teacher performance with “uncanny accuracy.” Only 0.5 percent of students provided answers that were insincere or inappropriate.

Matthews’s experience echoes the results of The Atlantic’s findings.

“I have some students who say things like ‘I wish we didn’t have to do so much math in this class,’” he said. “But I think high schoolers are mature enough to provide quality feedback, especially if you give them a few of the preemptive directions. I try to explain to separate their feedback from the grade they have in the class. A student could have an A and have legitimate issues with the class or have a C in a class and think the class is great.”

Sophomore Nikhil Bhasin believes student evaluations of teachers and their teaching styles would be beneficial.

“I think that there could be some good value in having students evaluate teachers regularly,” Bhasin said. “Students have a good sense of what works well, what is easy to understand and so on but are unable to convey that to many teachers.”

Despite the occasional irrelevant comment he receives, Matthews said that he believes student evaluations are useful.

“I emphasize that the more time and thought students put into their feedback, the more helpful it will be,” he said. “Looking at an individual student survey may not be super helpful, but if you look across the aggregate of all student surveys, I think you can get some good information.”

Allowing students a means to be critical about the quality of instruction they receive can only improve their success rates. Students have the most vested interest in their learning. After all, the quality of education affects their futures. So if we believe in measuring learning, perhaps we should also consider measuring teaching.

Nico Troedsson, a junior, is excited about contributing to Tideline for a third consecutive year, this time as a features editor. His passion for journalism...

Jonah Bahari, a senior, is returning to Pali’s Journalism program for his third and final year. He is ecstatic to serve as the head of the graphics department...