The Horrifying State of the Horror Movie

What happened to horror movies? What once existed as a genre defined by carefully constructed suspense and frights that at least entertained its audiences has been replaced by an enterprise characterized by vapid storylines and cheap jump scares. Horror films have not only been robbed of their intelligence, but, perhaps the more egregious offense, have been sucked of their entertainment value. Scary movie franchises stopped making releases that are even fun to watch, as each monotonous plot becomes more and more indistinguishable from its predecessor, leading to unimaginative twists that can be anticipated by watching a thirty second trailer.

However, this has not always been the case, nor are these offenses ubiquitous in the genre around the world. In the spirit of a recently-departed Halloween, not to mention a sincere concern for the state of the horror film, here is an incredibly short, not so incredibly subjective list of the smartest, most skillfully crafted horror movies of all time.

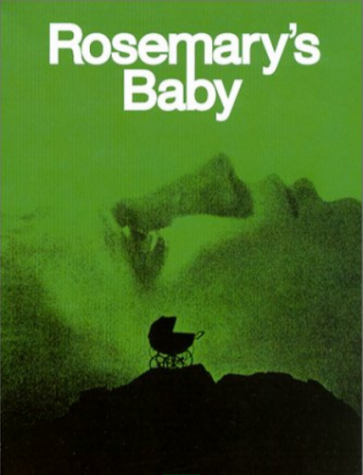

Rosemary’s Baby (1967)

This movie is beautiful. It’s intelligent, it’s well-shot, it’s suspenseful and, best of all, it’s scary. Roman Polanski’s 1967 classic is haunting, not because of some serial killer with an absurd backstory (looking at you AHS) or because of some murderous children’s doll or because of a demon that jumps out in front of our face. No. It’s haunting because of what it doesn’t put in front of us, because of what is concealed and left to the imagination of both the audience and the protagonist, a young, pregnant housewife portrayed by a stunning Mia Farrow. By about an hour in it’s clear that something is going on in the apartment next door, but just what that something is remains unclear. Farrow’s suspicions about the merry, fast-paced old neighbors with an affinity for late-night chanting leads the film down a rabbit hole of paranoia. By about two hours in, we don’t know if Farrow’s crazy or if we are for totally believing her.

This wonderful sense of paranoia is achieved not through easily recognizable signs served to the audience on a silver platter. It’s achieved through subtleties and cues — through the cries of a baby so faint and far away we can’t help but wonder if we’re imagining it. Through a slip-up in somebody’s sentence that plants doubt in Farrow. Through the misplacement of an object that could have either been the result of a mistake or of a carefully devised scheme. All of these create the doubt and haunting wonder that Polanski manufactures so skillfully. A brass-heavy score, oftentimes rising and rising to a sound which seems to a signify a horrifyingly imminent reveals leads to show…nothing. Like the silhouette in the “Psycho” motel window, these qualities produce suspense — a feeling scarier than fright ever could be.

A noticeable distinction between a film like Rosemary’s Baby and the big-budget horror movies of today is that Rosemary’s Baby has patience. Whereas Paranormal Activity 37 feels the need to skip right to the chase, rushing to the jump scare with the consequence of under-developed characters we simply don’t care about, Polanski’s film allows us to understand Farrow and her husband, to empathize with them — resulting in both a movie and a haunting, ending reveal that simply matters more.

Mulholland Drive (2004)

No, this movie isn’t typically placed in the horror genre. It is, however, horrifying.

My first attempt to watch this film was in July, at some run-down theater on Manhattan’s Lower East Side at 12 in the morning. Aside from M. Night Shyamalan’s 2015 atrocity, “The Visit,” this was the only time I’d left my seat mid-movie. I tried convincing myself that it was plainly bad, or that the writing was shoddy or the acting was sub-par. But after a week, it hit me: David Lynch had made one of the most genius films ever released. The reason I left was because the feeling that the movie exuded was so unnatural, it was unbearable to sit through.

The film doesn’t work in a traditional manner. Its characters are just a little too perfect, it sets a bit too pristine, its dialogue cleaner than it should be. It’s as if an alien took a crash course on human nature and wrote about it. Everything looks like it should and sounds like it should, but it doesn’t feel like it should. The feeling is inhuman, one that makes it seem as though you’re being watched for some reason. It’s terrifying.

A second attempt, a month later, ended in my finishing the movie. I still absolutely despised the sensation it gave me and, like the disturbed customer in the diner describing his nightmare, I too hope I never need to see it again. Nonetheless, I loved it. David Lynch’s directing is masterful. It’s the nearly frozen extras blurred from the foreground, the unnaturally natural mannerisms of the characters, the spark of life that has been so intricately put out from the film’s vision of Los Angeles that evoke this feeling. It is this attention to detail and style that’s missing from the popular horror movies of today. In order to craft a setting that is so unnatural, Lynch needed to know exactly what a natural setting felt like. This movie is horrifying because, within 2 minutes of the title sequence, you feel that you have no power anymore. You gave that up to David Lynch when you pressed play.

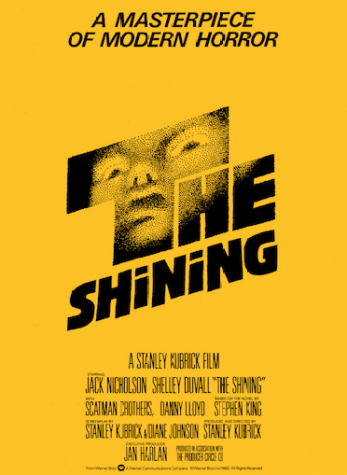

The Shining (1980)

Shut up, I don’t care if all anyone talks about is “The Shining.” There’s a reason for that.

If “Rosemary’s Baby” drags a toe across the surface of paranoia and insanity, “The Shining” cannonballs in. Perhaps the most haunting portrayal of madness ever dedicated to film, the movie itself is an experiment on the idea of narrative reliability. With each member of the Torrance family losing their grasp on reality more and more as their residency in solitude ticks by, who can be trusted by the end? The abusive, alcoholic father with a facade of sanity so frail it can be peered through before the title sequence rolls? The introverted boy with a hyperactive imagination? The wife living in fear of her husband, kept for weeks within the confines of the Overlook Hotel? No, none of them. By the appearance of the credits we aren’t even sure if we can trust our own judgment.

This is where the film derives the majority of its horror. The idea that, by simply being alone with our own thoughts for a little too long, anybody can go crazy. The plot isn’t terribly suspenseful — by the end of the first scene the foreshadowing is so blatant that it’s unlikely the story will veer too far away from what’s been hinted. However, this is not to say that suspense isn’t prominent. It’s the long-lens cameras that give the desolate corridors of the hotel a length which seems to denote that any number of things can be lying idly by. It’s the screeching, erratic music that reaches its climax as nothing particularly frightening occurs visually. These are elements of the nail-biting suspense that Kubrick expertly crafts into each sequence.

There aren’t ghosts (at least, there don’t appear to be ghosts.) There aren’t any jump scares. No demons, no possessed mannequins, no ouija boards. There’s just, as Kubrick said, a man and his family “quietly going insane together.”

Each year it seems, expectations for the season’s horror movies plummet further and further. The idea of a scary movie as being good regardless of its place in the “horror” genre is seen as a rarity. The notion of one being great feels almost laughable. This shouldn’t be the case. As the films on the list attest to, horror movies don’t deserve a double standard when it comes to caliber of the film-making. Hollywood just needs to start caring.